A comprehensive report on COVID-19’s threat impact shows the extent of cybercriminal attempts to hookwink vulnerable users.

Between January and March, coronavirus-themed phishing lures, malware infections, network intrusions, scams, and disinformation campaigns have become rampant across the clear, deep, and dark web.

Researchers from IntSights, a cybersecurity company, have collated a 12-page report summarizing the trending threats out there, including:

1. Registrations of phishing domains

In 2019, only 190 domains using the worlds ‘corona’ and ‘covid’ were registered. In January of 2020 alone, that number was over 1400, and during February, it soared to over 5000 before topping 38,000 in March.

2. Pandemic-linked phishing emails

Hackers impersonating government health agencies have been blasting our emails containing malware links to steal information.

3. Targeted malware

A Russian underground vendor is offering a malware that looks like the Johns Hopkins coronavirus outbreak map, which pulls real-time data from the legitimate site. The map is a JAVA-based malware deployment that installs the AZORult credential stealer malware. The kit costs $200 if the buyer has a Java code certificate, or $700 if the buyer wishes to purchase the seller’s certificate. The map mimics the real Johns Hopkins map, hosted at coronavirus.jhu.edu, and features live, real-time data.

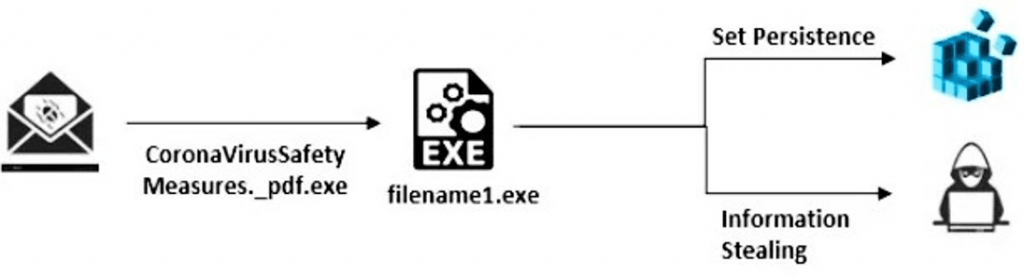

The Remcos RAT malware is spreading through unknown infection vectors to drop an executable file called “CoronaVirusSafetyMeasures_pdf[.]exe.” The file is an obfuscated dropper that would install the executable on the compromised computer with a VBS file specifically designed to run the RAT. The malware is capable of persistence through a startup key, which allows the malware to restart when the victim’s device is restarted. After installation is complete, the malware then logs the user’s keystrokes and exfiltrates the data to its command and control IP, 66[.]154.98.108.

Earlier in March, researchers discovered an Emotet phishing email circulating, designed to look like it is from China’s Ministry of Health. The email detailed official emergency coronavirus regulations, suspiciously in the English language. Natural language analysis revealed that the English was a very poor translation, reflecting incorrect grammar and including odd phrases, such as “As we work hard to kicking away the virus.” This indicates that the email was written by a non-English speaker. Attached to the email is an .arj file called “Emergency Regulation Ordinance,” which is a Windows RAR file.

When unpacked, a Windows Batch file called “Emergency Regulations” executes and proceeds to exfiltrate the victim’s user credentials to the Command and Control IP.

4. Ransomware and tactics

While some cybercrime groups vouched to not attack medical facilities during the outbreak, others had no such intentions. The Maze ransomware group, which has previously targeted everything from small US law firms to the German government, targeted HMR, a company that performs clinical tests for drugs and vaccines. The company was attacked on March 14th, with medical records of over 2,300 patients and employees leaked on 21 March.

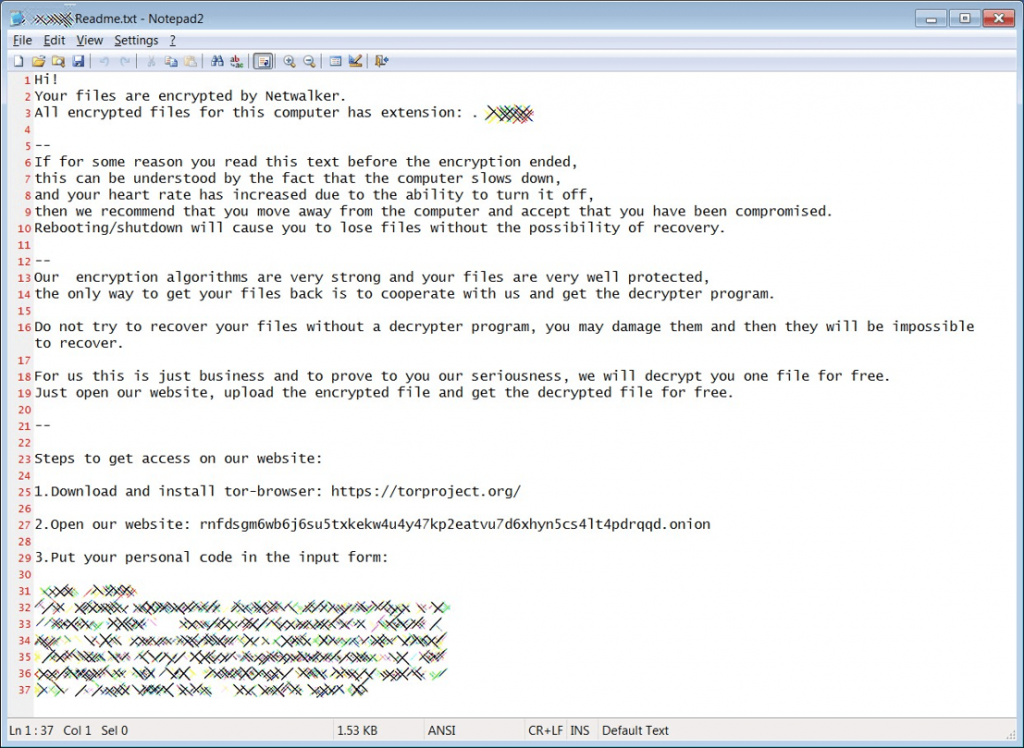

In early March 2020, the Champaign Urbana Public Health District (CHUPD) in Illinois was attacked by the NetWalker ransomware group. The campaign started with a coronavirus-themed phishing email loaded with a malicious attachment named “CORONAVIRUS_COVID-19.vbs.” The file contains an embedded NetWalker ransomware executable file and obfuscated code to extract and launch it on the victim’s device. The NetWalker ransom mail taunts the victim by insisting he or she move away from the computer and let the malware finish its encryption process, emphasizing there is nothing the victim can do to stop it.

One ransomware mail not only claimed that it had encrypted all of their victims’ data, but that they can also “infect your whole family with the Coronavirus.” These types of fear tactics work on a vulnerable population of people during a frightening pandemic. Threat actors use these fear tactics because they work. Researchers have also observed similar psychological tactics used in sextortion scams.

5. Fraud and hoaxes

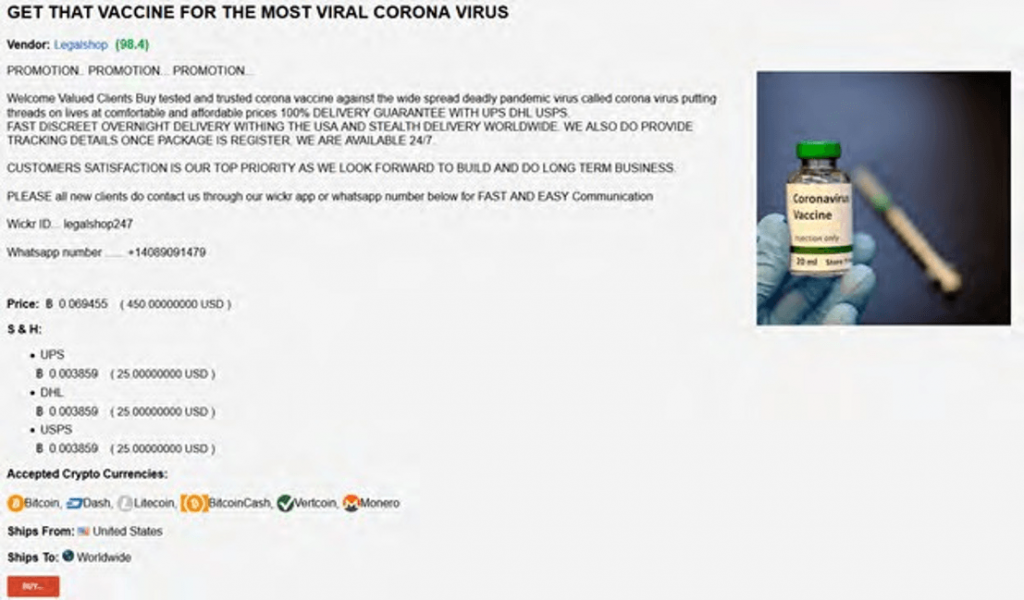

There has been a surge in COVID-19 related products, scam templates, and hoaxes on deep and dark web markets. The sellers seek to exploit public fear by offering products that could allegedly serve as virus tests or vaccines. The limited availability of coronavirus testing—especially in countries like the United States—leads to demand for such products in black markets. In all likelihood, however, these “products” are in no way real, and buyers would be scammed out of their money.

One particularly bleak offering, claimed to offer blood and saliva from a coronavirus survivor. In theory, this blood and saliva could impart immunity for the virus, as it may contain functional antibodies.

6. Fake mobile apps

Cybercriminals are creating a plethora of fake mobile apps claiming to provide useful pandemic. Researchers monitor multiple online app stores for fake apps, and while some of the fake apps that have been created are not harmful, others have malicious capabilities such as ransomware, trojans, spyware, and more.

7. Threats to remote-working

With a huge percentage of the global workforce now in work-from-home scenarios, there is a significant increase in the usage of online meeting platforms, and cybercriminals are paying attention. Cybercriminals are discussing different online platform vulnerabilities and exploits. With the majority of the workforce working from home and utilizing these platforms (sometimes on their personal computers as well), it is imperative to make sure these systems are secure and patched. Research data shows a massive rise in vulnerabilities from the Zoom video conferencing and Cisco Webex apps.

8. Disinformation and social engineering campaigns

Information about COVID-19 is pouring into the internet from every country and from various outlets, including governments, press, social media, healthcare professionals, and cybercriminals. As with any crisis, war, or other opportunity, threat actors are using the novel coronavirus to create panic, confusion, and distrust. Criminals have found ways to exploit human ignorance about coronavirus detection, testing, and treatment by selling various products and services that claim to help or heal people.

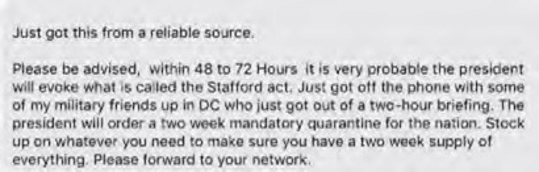

Social media is teeming with hoaxes, myths, and conspiracy theories about where the virus originated, who is to blame for its global spread, how it spreads among the population, and how it can be detected. Of greater concern is the spread of disinformation by state-sponsored operations to create dissent and disrupt world markets, elections, and authorities.

Politicians and militaries alike are employing psychological operations on adversary populations to cause conflict, division, and dissent around this pandemic. Whether it is a lie about an opponent in an election and how he is governing during this crisis, an authoritarian party censoring information to control the narrative, or a foreign nation trying to influence the world by placing blame for the origination of the virus, the tactics are difficult to detect and track.

What started as simple phishing attacks and hand sanitizer scams now involves several well-known threat actors. APT36, FIN7, the Maze ransomware group, and several other nation state actors are now behind attacks related to the coronavirus pandemic.

The report asserts that, as sophisticated threat actors enter this ring, both the volume and sophistication of the attacks will likely increase in the ensuing months.